The Iliad is book #3 from The Literary Project.

“Iliad” means “a poem about Ilium” (i.e. Troy), and The Iliad is one of the world’s most well-known narrative legends. Most everyone has heard of Troy and of swift-footed Achilles. Although he doesn’t enter battle until the very end, this epic is fully centered around his obstinate rage, as is evident by the opening line:

“Rage—Goddess, sing the rage of Peleus’ son Achilles.”

The Iliad was never originally a written poem, but an oral legend spoken from memory (can you imagine having such a robust memory?). It was performed orally for an audience, in a poetic language that was very different from everyday Greek of the time, and allowed for improvisation (which means there isn’t an exact original version). It is believed that the poem was altered and refined much over time, and as it was committed to writing. We can place its development to roughly 800 BCE – 750 BCE.

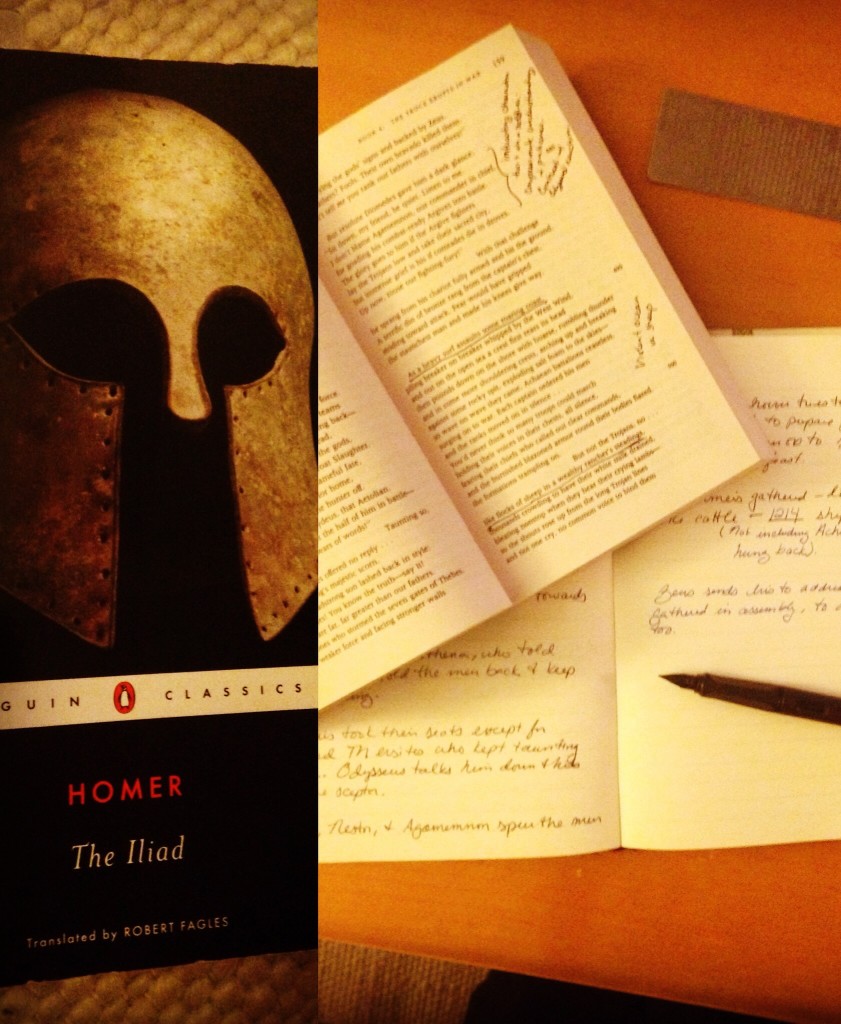

In trying to decide between various translations, I picked the translation by Robert Fagles after a sampling revealed it to be the most contemporary, and therefore the easiest syntactically (not that it was easy, but easiest relative to other translations, such as Robert Fitzgerald’s which sounds more Shakespearean). There are also many prose versions out there, but I decided that—short of reading the story in its original ancient Greek—I’d like my experience to be as close as possible to what it was meant to be: And Homer voiced this tale in verse, not prose.

Logic-Stage Analysis

In the English translations, there is no rhyme pattern. (the original Greek is in the form of a dactylic hexameter, which is traditional for epics but not very doable with the English language.) The lines and stanzas follow no pattern or formula—they all vary. Some are 3 lines long and others are 30.

Epics are known for repetition, but the key thing that I found highly repetitive wasn’t so much in the poem’s technical structure or form, but rather the detailed blood and gore:

“clean through heavy metal and bone the point burst

and the brains splattered all inside the casque.”

(Book 11, Lines 113-114)“Menelaus hacked Pisander between the eyes,

the bridge of the nose, and bone cracked, blood sprayed

and both eyes dropped at his feet to mix in the dust—“

(Book 13, Lines 708-710)“…he let fly

with a bronze-tipped arrow, hitting his right buttock

up under the pelvic bone so the lance pierced the bladder.”

(Book 13, Lines 749-751)“Idomeneus skewered Erymas straight through the mouth,

the merciless brazen spearpoint raking through,

up under the brain to split his glistening skull—

teeth shattered out, both eyes brimmed to the lids

with a gush of blood and both nostrils spurting,

mouth gaping, blowing convulsive sprays of blood

and death’s dark cloud closed down around his corpse.”

(Book 16, Lines 407-413)

While the details themselves varied, these kinds of descriptions go on and on for pages. I have to admit I did tire of it and found myself having to push through. But, if Homer’s intent was to impress the gruesome reality that is war onto his listeners—despite an audience that glorified it—I believe he may have succeeded.

There were many metaphors throughout as well, usually in the form of similes. Homer thrusts them in there, right in the middle of all the action. I usually had to pause and reread the metaphor from the beginning, as sometimes I would be two lines into it before I realized I was reading a metaphor and not literal verse.

There are countless places in which the fighters are likened to animals such as lions and boars, or sheep and cattle:

“As a lion charges cattle, calves and heifers

browsing the deep glades and snaps their necks,

so Tydides pitched them both from the chariot”

(Book 5, Lines 180-182)“Menelaus fierce as a mountain lion sure of his power,

seizing the choicest head from a good grazing herd.”

(Book 17, Lines 69-70)

Sometimes they are likened to natural forces:

“Wild as a swollen river hurling down on the flats,

down from the hills in winter spate, bursting its banks

with rain from storming Zeus, and stands of good dry oak,

whole forests of pine it whorls into itself and sweeps along

till it heaves a crashing mass of driftwood out to sea—

so glorious Ajax swept the field, routing Trojans,

shattering teams and spearmen in his onslaught.”

(Book 11, Lines 580-585)

Pulling in at 538 pages, this heavyweight literary champion took me 3 months to get through. And I’m a fast reader too. It was a fulfilling experience, and, I must admit, I feel a deep sense of accomplishment.

Rhetoric-Stage Analysis

The epic opens in the 10th year of the war. The Greeks have just plundered a nearby ally of Troy and have divvied up the goods, including the women. Agamemnon made the mistake of taking the daughter of one of Apollo’s priests, causing the wrath of Apollo to rain a plague down on the army. Agamemnon was forced to return her to appease the god and halt the plague, but since Achilles was especially vocal in insisting on this solution, Agamemnon decides to pick on him and takes Achilles’ slave bride for himself to make up for his own loss. This is a deep dishonor and emotional wound to Achilles. The level of insult is profound, and Achilles not only vows to discontinue fighting—withdrawing all his men from battle completely—he prays to his mother, the sea goddess Thetis, to persuade Zeus to help the Trojans beat the Acheans (The Acheans are all the various Greek allies fighting against the Trojans. They are also called “Argives”).

Achilles explains his humiliation in-depth to Patroclus right before Patroclus fights and dies:

“this terrible pain that wounds me to the quick—

when one man attempts to plunder a man his equal,

to commandeer a prize, exulting so in his own power.

That’s the pain that wounds me, suffering such humiliation.

…

How on earth can a man rage on forever?

Still, by god, I said I would not relax my anger,

not til the cries and carnage reached my own ships.”

~Achilles

(Book 16, Lines 60-63 & 70-72)

I have to admit I didn’t like Achilles much. I found him to be selfish and stubborn in his unrelenting anger. But this characterization, ironically, raises Achilles to godlike stature (which, technically, he is half god with a sea goddess for a mother). Just as I found the gods to be selfish and petty, so Achilles seemed to me the same. Great Ajax and Hector—humans—were much more noble characters who cared for their comrades. Achilles cares nothing for his fellow Argives—he is rage.

There are two points in the story where any change occurs within the rage of Achilles: one in which his rage is transferred to another individual, and one in which his rage is finally suspended altogether.

Achilles Finally Let’s Go of His Rage Against Agamemnon

The first catalyst is when his brother-in-arms, Patroclus, is killed by Hector. Only when his rage against Hector supersedes his rage against Agamemnon, is when a change takes place: Achilles will finally join the fight. He swears off his anger:

“Agamemnon—was it better for both of us, after all,

for you and me to rage at each other, raked by anguish,

consumed by heartsick strife, all for a young girl?

…

Better? Yes—for Hector and Hector’s Trojans!

Not for the Argives. For years to come, I think,

they will remember the feud that flared between us both.

Enough. Let bygones be bygones. Done is done.

Despite my anguish I will beat it down,

the fury mounting inside me, down by force.

Now, by god, I call a halt to all my anger—

it’s wrong to keep on raging, heart inflamed forever.”

~Achilles

Book 19: Lines 63-65, 71-78)

But even then, he has not transformed in any meaningful way. He is still nothing but rage; this time rage towards Hector. And this rage brings the end to Hector’s life.

Achilles Finally Suspends His Rage Completely, and Feels Compassion

The second catalyst is when Priam, the father of Hector, risks his life and sneaks into the enemy camp, arriving at Achilles’ tent in the middle of the night to beg for the body of his son:

“The majestic king of Troy slipped past the rest

and kneeling down besides Achilles, clasped his knees

and kissed his hands, those terrible, man-killing hands

that had slaughtered Priam’s many sons in battle.

…Achilles marveled, beholding majestic Priam.”

(book 24, Lines 559-567)

Priam reminds Achilles of his own father. This is the point at which Achilles finally lets go of his rage completely, and we witness compassion taking its place:

“remember your own father! I deserve more pity…

I have endured what no one on earth has ever done before—

I put to my lips the hands of the man who killed my son.”

~Priam

(Book 24, Lines 589-591)“and filled with pity now for his gray head and gray beard,

he spoke out winging words, flying straight to the heart:

‘Poor man, how much you’ve borne—pain to break the spirit!

What daring brought you down to the ships, all alone,

to face the glance of the man who killed your sons,

so many fine brave boys? You have a heart of iron.

Come, please, sit down on this chair here…’”

(Book 24, Lines 603-609)

But there is a delicacy in the situation. Achilles, even in his newfound compassion, is wise enough to know that anger can break out again at any second:

“Then Achilles called the serving-women out:

‘Bathe and anoint the body—

bear it aside first. Priam must not see his son.’

He feared that, overwhelmed by the sight of Hector,

wild with grief, Priam might let his anger flare

and Achilles might fly into fresh rage himself,

cut the old man down and break the laws of Zeus.”

(Book 24: Lines 682-687)

Thus Priam is able to take Hector’s body home, and his burial ends the poem. The fall of Troy, we are to understand, will soon follow.

My Favorite Quotes

Here’s a list of some lines that especially jumped out at me as being useful even outside of context. A little ancient Greek wisdom if you will.

“hold in check

that proud, fiery spirit of yours inside your chest!

Friendship is much better. Vicious quarrels are deadly—

put an end to them, at once.”

~Peleus, as told by Odysseus

(Book 9, Lines 309-312)“no false respect. Don’t pass over the better man

and pick the worse. Don’t bow to a solder’s rank,

an eye to his birth—even if he’s more kingly.”

~Agamemnon

(Book 10, Lines 278-280)“Fight for your country—that is the best, the only omen!”

~Hector

(Book 12, Line 281)“One can achieve his fill of all good things,

even of sleep, even of making love…

rapturous song and the beat and sway of dancing.”

~Menelaus

(Book 13, Lines 733-735)“Past his strength

no man can go, though he’s set on mortal combat.”

~Paris

(Book 13, Lines 911-912)“Be men, my friends! Discipline fill your hearts!

Dread what comrades say of you here in bloody combat!

When men dread that, more men come through alive—

when soldiers break and run, good-bye glory,

good-bye all defenses!”

~Great Ajax

(Book 15, Lines 651-655)“the proof of battle is action, proof of words, debate.”

~Patroclus

(Book 16, Line 732)“So now, each of you, turn straight for the enemy,

live or die—that is the lovely give-and-take of war.”

~Hector

(Book 17, Lines 261-262)“Breathing room in war is all too brief.”

~Iris (messenger goddess)“when a man stands up to speak, it’s well to listen,

Not to interrupt him, the only courteous thing.

Even the finest speaker finds intrusions hard.”

~Agamemnon

(Book 19, Lines 91-93)