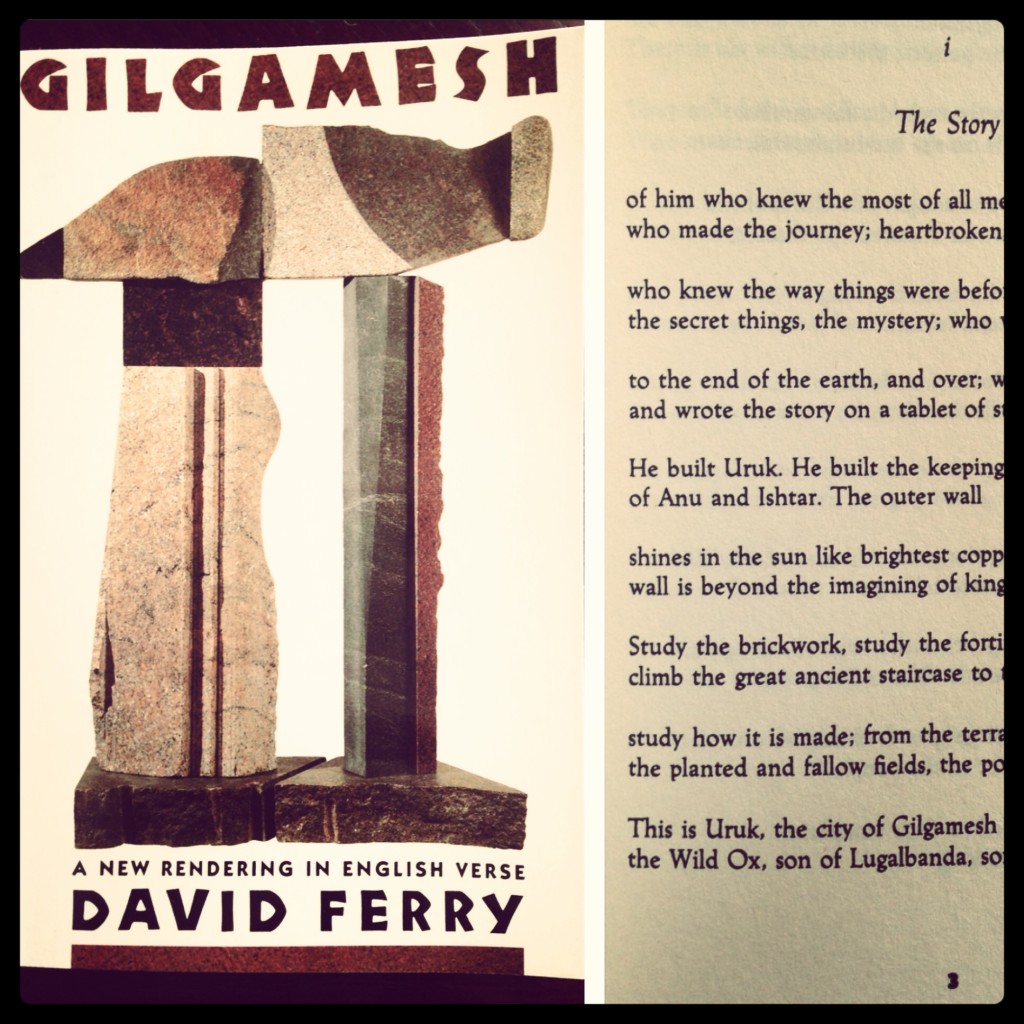

Gilgamesh is book #1 from The Literary Project.

The Epic of Gilgamesh is a Sumerian poem from ancient Mesopotamia, and considered the world’s first great work of literature. Although the exact date of its first existence is up for debate, we can generally say it’s from sometime around 2,000 BCE (give or take a couple hundred years).

The epic is a story about Gilgamesh, the king of Uruk (an ancient city of Sumer), and his enemy-turned-brotherly-friend, Enkidu. The two of them fight epic battles against monsters, incite the anger of the gods, and face the reality of impermanence: death.

While the epic itself is mythical, Gilgamesh is a real historical figure who is listed in the Sumerian King List (the oldest historical record in the world, set down on tablets around 2100 BCE). He really was a king of Uruk who usurped the throne around 2700 BCE.

Logic-Stage Analysis

[Note: Gilgamesh, being an epic poem, is a chronicle with a beginning, middle, and end, except for the very last tablet (XII), which seems to have been tacked onto the end much later in time because not only is it its own story apart from all the rest, it contradicts the original story. I decided not to address it it my analysis.]

The epic begins with the overarching idea that Sumerians are conflicted about kingship (Gilgamesh is strong—“two-thirds a god, one-third a man”—…but oppressive: “Aruru is the maker of this king. Neither the father’s son nor the wife of the noble is safe is Uruk; neither the mother’s daughter nor the warrior’s bride is safe. The old men say: ‘Is this the shepherd of the people? Is this the wise shepherd, protector of the people?..’”), but primarily, the epic is evocative of the idea of immortality (“The life of man is short”).

Although many imagine epics as difficult to read, the diction in this one is very natural (A random selection as an example: “With the first light of the early morning dawning, in the presence of the old men of the city”). One will find David Ferry’s translation easy to read. Only through some of the dialogue does the syntax become a bit more poetic (as in the lamentation over Enkidu’s death: “May the wild ass in the mountains braying mourn. May the furtive panthers mourn for Enkidu…Euphrates mourn whose pure river waters we made libations of, and drank the waters…”). the poem is highly repetitive, with many stanzas repeating multiple times (which can be a bit annoying…).

Overall, it is a simple and pleasurable read. One gains a sense of accomplishment from having read a classic without having to slog through 600 pages.

Rhetoric-Stage Analysis

What follows are discussions on three different ideas that stood out to me throughout the poem.

Seeking immortality (the primary theme):

The poem’s primary theme consists of a tension between the earthly and the spiritual. there is a resistance, a constant wrestling with the reality of death by the seeking of immortality. at first, Gilgamesh simply has the goal of leaving a legacy:

Tablet II.v: “If I should fall, my fame will be secure.” And “My fame will be secure to all my sons.”

With this idea in mind, Gilgamesh embarks with Enkidu to the Cedar Forest to challenge its guardian, Hawawa. The entering of the forest is, ironically, marked by much fear and only serves to magnify their awareness of their mortality:

Tablets IV|V.ii: “The life of man is short….Protect us as we pass through fearfulness.”

The prayers of both Gilgamesh’s mother and Gilgamesh himself are answered: the sun god, Shamash, intervenes in the battle by unleashing “13 winds” against Huwawa, thereby weakening him and enabling Gilgamesh and Enkidu to kill him together. They return with a monument gate built from the tallest cedar tree, ensuring the legacy Gilgamesh sought. But having this legacy has proven not to be enough to rid them of their fear of death. Not only that, but after angering Ishtar for refusing her, she unleashes the Bull of Heaven to kill Gilgamesh—whereby he and Enkidu kill the bull. As a result, their fear of death is confirmed: the Gods have decided that Enkidu must die to pay the price for their killing the Bull of Heaven. Their fear is only intensified, and turns to anger:

Tablet VII.ii: “Gilgamesh listened to him and weeping said: ‘The stormy heart of Enkidu the companion rages with understanding of the fate the high gods have established for mankind.’”

Enkidu dies and Gilgamesh seeks to immortalize him by having a statue of him made. Gilgamesh, mourning for Enkidu and seeing how he died, laments his own fate:

Tablet IX.i: “’Enkidu has died. Must I die too? Must Gilgamesh be like that?’”

Gilgamesh then decides he will find Utnapishtim—the man who escaped the Great Deluge and the only man who has ever found immortality. Gilgamesh is determined to find out his secret. On his journey, he must pass through The Mountain Mashu, wherein the entirety of Episode iii within Tablet IX is dedicated to his traveling the long, long length of darkness through the mountain Mashu. The darkness of this episode is symbolic of death.

When he reaches the garden beach on the other side, the resident tavern keeper, Siduri, reminds him of the reality he must accept:

Tablet X.i: “Thin veiled Siduri replied to Gilgamesh: ‘Who is the mortal who can live forever? The life of man is short. Only the gods can live forever.’”

Of course Gilgamesh still refuses the truth, and continues on. He crosses the sea and finds Utnapishtim on the island. Utnapishtim, in a long monologue, speaks to Gilgamesh of the truth of impermanence:

Tablet X.v: “…How long does a building stand before it falls?…How long is the eye able to look at the sun?”

Eventually, Utnapishtim relents, and gives Gilgamesh instructions on how to obtain the Magical Plant of Youth, which he does by diving deep into the water (Tablet XI.vi).

Right as he has obtained the immortality he so long sought after, it is stolen away by a serpent! (Tablet XI.viii). At this point, he is resigned. He reluctantly admits that the efforts to avoid death are futile:

Tablet XI.viii: “I descended into the waters to find the plant and what I found was a sign telling me to abandon the journey and what it was I sought for.”

And thus, finally changed—accepting of the truth of impermanence—he returns to Uruk.

Genesis retold…or told here first:

I could not help but draw some parallels between The Epic of Gilgamesh and The Book of Genesis. At first my thinking was that Genesis was being retold here, until I realized that Gilgamesh was, in fact, written before Genesis. Did the author of Genesis ever hear of the story of Gilgamesh? (The tablets were not discovered until the 1800s, but back then stories were passed on orally for centuries, even with the invention of writing.) Perhaps this story is simply universal—an inherent part of the human condition? (“This story” being, simply: a loss of innocence due to a gain in knowledge, and a loss of immortality as payment for that knowledge.) I doubt we will ever know, but here is my analysis on the parallels:

Tablet I: Shamhat (Eve) brings Enkidu (Adam) “fruit,” causing him to lose his innocence. As a result, he gains knowledge, much as the fruit eaten by Adam and Eve was of the Tree of Knowledge.

Tablet I.iv: “in the mind of the wild man was beginning a new understanding” and “whose heart was beginning to know about itself.”

As a consequence, he must leave the wild, for all the beasts now flee from him (banishment from Eden).

Then, in Tablet XI.viii: The Plant of Immortality is stolen by a serpent. This stealing of immortality by a serpent parallels the serpent in The Garden of Eden, who is the one who convinced Eve to eat of the forbidden fruit, and ultimately the one who caused Adam and Eve’s loss of immortality.

Enkidu & Gilgamesh lovers?

OK, now perhaps this one is a little out there, but I couldn’t help but notice little hints that maybe, perhaps, Enkidu and Gilgamesh were lovers, rather than like brothers. After their first fight, when they make-up, they “embraced, and kissed, and took each other by the hand.” (First in Tablet II|III.iii, but it occurs several times) Now, granted, what was considered culturally acceptable between hetersexual men has changed greatly over time. So, I am not implying this as proof, but merely an alternate interpretation to their relationship.

At Enkidu’s death, Gilgamesh is feminized, metaphorically compared to a woman and then to a lioness as he grieves for Enkudu, and Enkidu is referred to as “companion” rather than, say, “brother,”, and likened to a “bride”:

Tablet VIII.i: “It is Enkidu, the companion, whom I weep for, weeping for him as if I were a woman.” “Gilgamesh covered Enkidu’s face with a veil like the veil of a bride. He hovered like an eagle over the body, or as a lioness does over her brood.”

Later on his journey, when Gilgamesh is speaking with the tavern keeper, Siduri, he speaks of his love for Enkidu, referring once again to Enkidu as his “companion” and himself as a “woman”:

Tablet X.i: “Enkidu, the companion, whom I loved, who went together with me on the journey no one has ever undergone before.” “Weeping as if I were a woman I roam the paths and shores of unknown places…”

These were the only hints I found to support this theory. Again, just a theory, and, I think, an interesting perspective on the story.