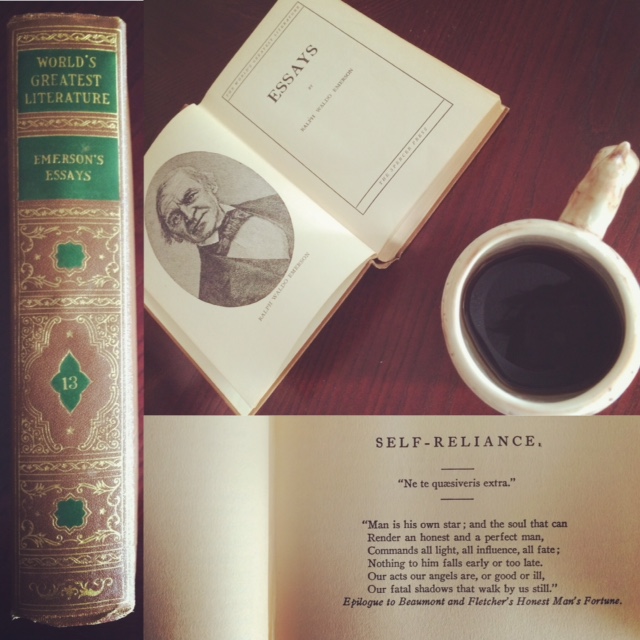

This essay was part of the 2016 Deal Me In Reading Challenge, where I read a short story, essay, or poem every single week. Each item on my reading list was assigned to a playing card, and every Friday I picked a card at random to choose my weekly read.

As I slowly cracked my old 1936 volume Emerson’s Essays from the World’s Greatest Literature collection (of which I, sadly, only own 3 random volumes picked out of a droopy cardboard box at a garage sale), I strained myself mentally to read Self-Reliance and found myself exposed to an unexpected whiplash of principles.

Yes, yes!…

–Ugh, so selfish….

–Bravo! I couldn’t have worded that any better!…

–Oh boy. This is…this is actually a very pernicious philosophy.

I had just recently read Tao Te Ching, within which Lao Tzu’s ideas on government ignited red alarm bells within my American mind; and now here I was on the opposite end of the collectivism-individualism spectrum reading one of the most famous essays by an American intellectual: while truly identifying with some of his points, I was simultaneously repelled by others.

The level of self-centered pride within much of the essay made me wonder if this is where Ayn Rand may have gotten all of her ideas.

On Self-Trust

Waldo Emerson begins with the concept of self-trust. This was one of the things that resonated with me in a positive way.

Have you ever been in a classroom or in a conference room when you have an idea, a thought, or a question, but you keep it to yourself because you’re so afraid it’s stupid? Because of course everyone else “obviously” knows so much more than you? And then the “smart kid” in class, or the senior colleague with years of experience under her belt, speaks up…and she says precisely what it was you were thinking?

“A man should learn to detect and watch that gleam of light which flashes across his mind from within, more than the lustre of the firmament of bards and sages. Yet he dismisses without notice his thought, because it is his. In every work of genius we recognize our own rejected thoughts: they come back to us with a certain alienated majesty.” [emphasis added]

Yeah. That.

Or what about when you’ve come up with new ideas that are completely different to what you had originally, or (gasp) you’ve changed your opinion on something due to further reflection, but you’re so afraid of being judged capricious by others that you stay mum, or worse, keep pretending that you’ve retained all your original perspective?

“The other terror that scares us from self-trust is our consistency; a reverence for our past act or word, because the eyes of others have no other data for computing our orbit than our past acts, and we are loath to disappoint them.”

In other words, it is perfectly OK to change your mind:

“Speak what you think now in hard words, and to-morrow speak what to-morrow thinks in hard words again, though it contradict every thing you said to-day.”

Social pressure to avoid embarrassment or to never change can be intense. Self-trust is a simple concept, but can be surprisingly difficult to implement.

“Trust thyself: every heart vibrates to that iron string.”

On Conformity

Building further on self-trust, Waldo Emerson was staunchly anti-conformist:

“Society is a joint-stock company, in which the members agree, for the better securing of his bread to each shareholder, to surrender the liberty and culture of the eater. The virtue in most request is conformity…Whoso would be a man must be a nonconformist…Nothing is at last sacred but the integrity of your own mind.”

But then he veers into iffy territory. One should be so only like themselves and throw off the bow lines of conformity completely, so that only what fits into one’s own psychology is what is “right”:

“Good and bad are but names very readily transferable to that or this; the only right is what is after my constitution, the only wrong what is against it.”

To say that “the only right is what is after my constitution,” signals psychological and emotional immaturity. It indicates an inability to tolerate the “inconvenience” of interacting with people who are different than ourselves (an inevitability when one moves through the world), because now things aren’t going the way that I want them to be.

“I appeal from your customs. I must be myself. I cannot break myself any longer for you, or you. If you can love me for what I am, we shall be the happier. If you cannot, I will still seek to deserve that you should. I will not hide my tastes or aversions.”

Customs and etiquette developed originally as a result of the effort to be civil towards each other’s varying sensibilities. Their purpose is to help us be respectful and decent to other human beings, who are no less valuable than ourselves. While it’s my belief we must each accept and be ourselves, it is also my belief that if someone is outright rude, imposing, or insensitive towards others, they cannot simply say “I must be myself,” and think it is all right.

Emerson is painting a false dichotomy: either be a slave to society or be free from it. He doesn’t make any room for a middle ground, and the polarized choice he has settled on seems highly self-centered.

On Solitude

“It is easy in the world to live after the world’s opinion; it is easy in solitude to live after our own; but the great man is he who in the midst of the crowd keeps with perfect sweetness the independence of solitude.”

I love this quote. Because it is easy to just live after the world’s opinion without question, especially in this highly digitally distracting world that we have allowed to virtually eliminate the arts of reflection and introspection. I would only add one caveat: that the independence of solitude is not for nonconformity’s sake; that it is perfectly OK if the conclusions we have drawn after quiet deliberation happen to agree with prevailing beliefs.

But in the pursuit of solitude, Emerson acts as though he’s the only person that matters:

“I shun father and mother and wife and brother, when my genius calls me…Expect me not to show cause why I seek or why I exclude company.”

Solitude is wonderful. I especially understand the need for it because I’m an introvert…but I still think it’s courteous to explain to my husband or those around me if I’m in need of it, rather than disappear without a word. What if they had wanted to spend time with me? In relationships, communication and compromise are vital, but Waldo Emerson doesn’t seem to think so.

On Speaking Your Mind

So by now I’m sure you’ve realized that Emerson isn’t too highly concerned with other people’s feelings. (I could be completely wrong of course. I have not read any biography or accounts about what he was like. This is simply the strong sense I got from reading this essay.)

“…truth is handsomer than the affectation of love. Your goodness must have some edge to it,–else it is none.”

He must’ve been a harsh, blunt friend indeed. In fact, with regards to friends, he says:

“I cannot sell my liberty and my power, to save their sensibility.”

On Prayer

Of course, as a Transcendentalist, he makes references to the divine and to prayer. Transcendentalists seem to believe in unity, in the belief that we all have divinity within ourselves:

“But prayer as a means to effect a private end is meanness and theft. It supposes dualism and not unity in nature and consciousness. As soon as the man is at one with God, he will not beg. He will then see prayer in all action.”

But a disclaimer: this is my first-ever reading of a non-fiction work by a transcendentalist, and I had to look up various definitions of what Transcendentalism even is.

On Technology as Crippling

And finally, Waldo Emerson made some interesting notes on technology and how it simultaneously helps and hinders us. Technology is both a boon to society, and a crutch on which we lean allowing our abilities to atrophy:

“The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet…A Greenwich nautical almanac he has, and so being sure of the information when he wants it, the man in the street does not know a star in the sky…His note-books impair his memory; his libraries overload his wit; …and it may be a question whether machinery does not encumber…”

And he goes on to wonder at how the best discoveries in the world were made with older technologies, before our natural physical and mental strengths were lessened:

“The harm of the improved machinery may compensate its good. Hudson and Behring accomplished so much in their fishing-boats, as to astonish Parry and Franklin, whose equipment exhausted the resources of science and art. Galileo, with an opera-glass, discovered a more splendid series of celestial phenomena than any one since. Columbus found the New World in an undecked boat. It is curious to see the periodical disuse and perishing of means and machinery, which were introduced with loud laudation a few years or centuries before.”

In many ways, I think this is true. We have grown soft (witness the obesity epidemic and our high levels of unnatural sedentariness), we have grown unable to find our own way around (GPS), we have lost our ability to focus and think deeply (the science is clear about the dopamine-rush effects of social media usage), and we have lost our ability to communicate with other human beings (just look around in any restaurant and you’ll see a ton of people staring at their phones while ignoring their dinner companions).

But this is not some inherent evil of technology. Technology is simply a tool–one which has increased the quality of life for humans by orders of magnitude. We simply have to be more deliberate in how we choose to use it–to not rely on it too much, and learn to rely on ourselves more.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), a Harvard-educated essayist and lecturer, was the center of the American Transcendentalist movement. Transcendentalism–as best as I can explain it–was a movement from the 19th century that saw knowledge as mentally and spiritually experiential, “transcending” above the physical senses. The philosophy also took a progressive stance on abolition, women’s rights, and education. Emerson suffered many tragic losses: his father, all his brothers, his first wife, and finally his 5-year-old son (the eldest of four from his second marriage). Professionally, he started out as a Pastor but resigned shortly after his first wife’s death. He then made a living as a writer and lecturer for over 40 years, was immersed within intellectual circles, and traveled the entire country east-to-west delivering hundreds of lectures.