This essay was part of the 2016 Deal Me In Reading Challenge, where I read a short story, essay, or poem every single week. Each item on my reading list was assigned to a playing card, and every Friday I picked a card at random to choose my weekly read.

This piece was originally published by the Tribune on October 19, 1945–right on the heels of the end of the Second World War and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan. This past August 6th & 9th, 2015, were the 70th anniversaries for the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, respectively. It’s a funny coincidence that I happened to draw this card this month, because President Obama is scheduled to speak at Hiroshima in 2 days–being the first sitting American president to do so.

For those who wish to read George Orwell’s essay in full, I found a copy of the essay here.

Orwell poses “the question that is of most urgent interest to all of us,” around which his essay revolves:

“How difficult are these things to manufacture?”

“…it appears from President Truman’s remarks, and various comments that have been made on them, that the bomb is fantastically expensive and that its manufacture demands an enormous industrial effort, such as only three or four countries in the world are capable of making. This point is of cardinal importance.” [emphasis added]

He goes on to point out how human history tends to be driven by weapons, and that the type of weapons in existence are significant to whether people have liberty or whether they are controlled by governments:

“I think the following rule would be found generally true: that ages in which the dominant weapon is expensive or difficult to make will tend to be ages of despotism, whereas when the dominant weapon is cheap and simple, the common people have a chance.”

He does preface this by saying, “I have no doubt exceptions can be brought forward,” but it elicited an eyebrow raise from me nevertheless. I wondered how far back into history he dove when he formulated this idea, because the fact remains that for most of human civilization–since its birth in the Fertile Crescent thousands of years ago–many governments and tyrants have managed to forcefully impose their rule with nothing but cheap & simple spears, axes, and bows & arrows: the Scorpion King of upper Egypt who conquered his foes in the north, Gilgamesh the usurper who crowned himself King of Kish, Sargon the first military dictator who employed an army to conquer Sumerian lands and establish the Akkadian empire…the list could go on, but these are some of the first accounts going as far back as 3,000 BCE.

Orwell goes on to state

“for example, tanks, battleships and bombing planes are inherently tyrannical weapons, while rifles, muskets, long-bows and hand-grenades are inherently democratic weapons.”

Ah…so while I disagree with his rule as he had written it, perhaps the tables turn in favor of the people when such cheap and simple weapons become explosive in nature. This is perhaps what he truly means, as he points out how the invention of the musket enabled the American and French revolutions, and other fights for independence:

“Even the most backward nation could always get hold of rifles from one source or another, so that Boers, Bulgars, Abyssinians, Moroccans—even Tibetans—could put up a fight for their independence, sometimes with success.”

I take issue with his use of the adjective “backward” for these nations. Just because they are not industrialized, does not make them “backward.” But I digress…

Orwell predicts what will happen in the future:

“So we have before us the prospect of two or three monstrous super-states, each possessed of a weapon by which millions of people can be wiped out in a few seconds, dividing the world between them….But suppose—and really this the likeliest development—that the surviving great nations make a tacit agreement never to use the atomic bomb against one another? Suppose they only use it, or the threat of it, against people who are unable to retaliate?” [emphasis added]

And indeed, of course, we now have the international Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons “whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation in the peaceful uses of nuclear energy, and to further the goal of achieving nuclear disarmament and general and complete disarmament.”

He was partially correct: the nuclear-weapon states did come to an agreement never to use the atomic bomb against one another, but this agreement is treaty-official and not “tacit,” and the countries in question do not have any real trust in each other, which means the likelihood that they would team up to “use [the bomb], or the threat of it, against people who are unable to retaliate” is incredibly unlikely; for the reason, not least of which, that any such threat from one of the nuclear-weapon states towards any country in the world would be considered a threat by everyone. That is how things currently stand, anyway. Who knows what such things will be like several hundred years from now (if we haven’t blown “civilisation to smithereens” by then)?

Orwell goes on to lament the cons that came with the invention of the airplane and radio technologies:

“We were once told that the aeroplane had ‘abolished frontiers’; actually it is only since the aeroplane became a serious weapon that frontiers have become definitely impassable. The radio was once expected to promote international understanding and co-operation; it has turned out to be a means of insulating one nation from another.”

Abolishing borders and promoting international communication? Sounds like the internet to me. I wonder what he would have said about that, considering the fact that it’s been a great democratizing force.

Towards the end of the essay, I felt as though I was reading the beginning inklings of his dystopian novel 1984 (which was published almost 4 years after this essay):

“We may be heading not for general breakdown but for an epoch as horribly stable as the slave empires of antiquity…few people have yet considered its ideological implications—that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of ‘cold war’ with its neighbors.”

He warns that we will live with:

“…the cost of prolonging indefinitely a ‘peace that is no peace’.”

*shudder*

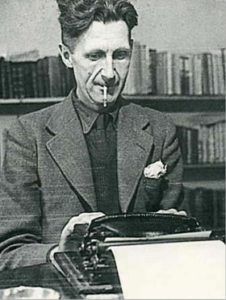

George Orwell

“George Orwell” was actually the pen name for Eric Arthur Blair. He loved the River Orwell in Suffolk, and so took the name for himself. He served as a WWII correspondent, and is most famous for his novels Animal Farm (published 2 months prior to this essay) and 1984 (published 4 years after), although he wrote an incredible number of essays. He died of tuberculosis about 6 months after 1984 was published.